The creation of art is as old as time. As long as humans have been around, art has been created, from hieroglyphs on the inside of cave walls carved by the ancients to the portrait of Mona Lisa painted by Leonardo DaVinci. In every case, art was created with a purpose to portray a specific person, idea, or abstract representation or to appeal to the viewer’s emotions in a specific way. Some of the most interactive art are sculptures that are presented in a way in which the audience can explore and connect with the piece. One of the best environments for contact with sculpture is in a sculpture garden outdoors, where the art is readily available and it can interact with its surroundings as well as the people walking through. One such garden is the sculpture garden associated with the Sheldon Art gallery.

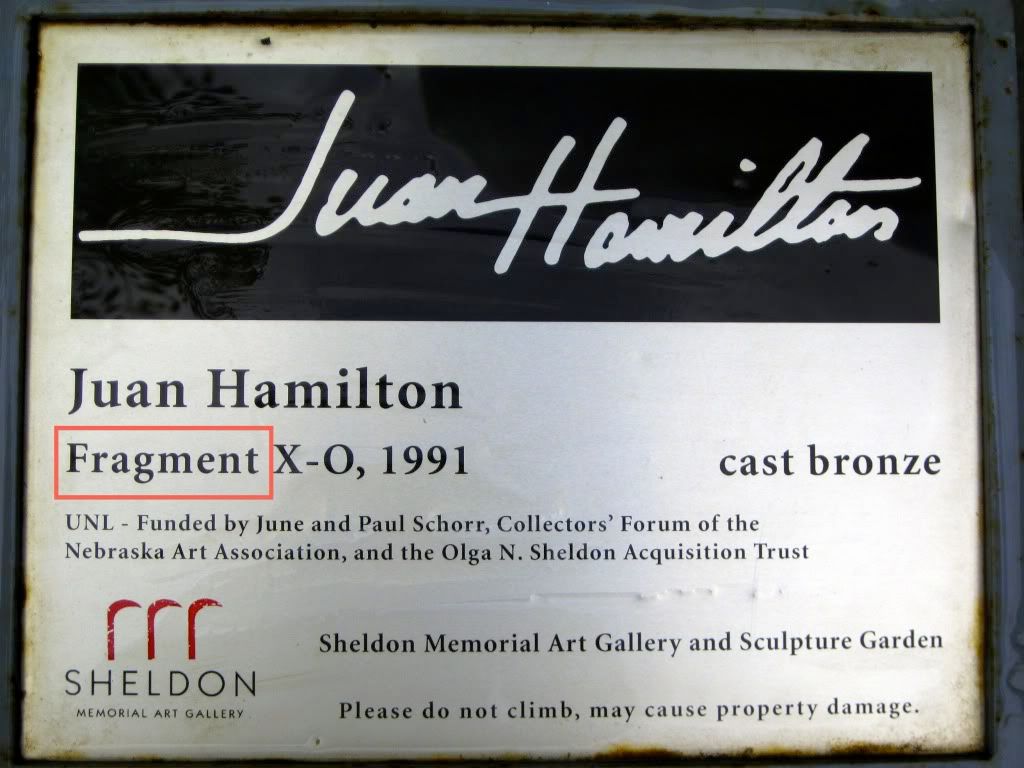

One of the most intriguing pieces of art in the garden is Fragment X-O by Juan Hamilton. Juan Hamilton is an artist that began his career by working with clay and creating pottery. He eventually moved into working with the bronze exemplified by Fragment after he went to study under Georgia O’Keefe during her final years. His art was greatly influenced by hers in the sensual and fluid shapes that appeared in her paintings. Fragment was also highly influenced by the aesthetics of Zen Buddhism that Hamilton encountered while on a trip in Japan, as much of his art is. Hamilton was also fascinated by how his sculptures interacted with the environment, whether that is indoors or out. Similarly, all of Hamilton’s abstract sculptures were created with meaning and how he was influenced the world around him. Fragment X-O is a counterargument for the symbolism of unity and completeness that is applied to the shape of the circle by western culture. This argument is formed through the contrast created in the pathos of the aesthetic elements and the rhetorical use of logos in the title and arrangement of elements.

The most obvious part of any art object is the physical and aesthetic portions. One of the first things that is noticed about Fragment is that it is formed out of bronze. This bronze has interacted with the weather and the environment in which it is located in an interesting way. Through the weathering process a variety of different hues have arose on the patina of the sculpture. First of all, a saturated and dark red hue has developed on the inside of the ring. On the top outside a slightly unsaturated teal hue has developed. However, the dark bronze color has remained on portion of the sculpture that is closest to the ground. These hues all sit on opposite sides of the color wheel, which according to Compose, Design, Advocate “have the most contrast.” (Wysocki and Lynch 275). This contrast in the patina that is created through the various hues not only adds interest to the simple structure, but speaks to the counterargument as well. This coloration creates a sense of discord within the viewer that parallels the disagreement that the sculpture is creating between the symbolism that is applied by westerners and other views.

Another aspect of the sculpture, which works to aid in the pathos, is the interaction of it with the environment in regards to lighting. One of the most important parts of the sculpture is its location outdoors. It interacts differently not only with the people that view it, but also the sunlight or lack thereof. On a bright, sunny day the sculpture seems to capture the light and then exude it outwards again. This makes the audience feel warm calm and tranquil as the light reflects off the soft curves. However, on a dull cloudy day the colors are dulled and the large “O” seems mysterious and foreboding. This contrast that is altered by the change in the weather also works to aid in the counterargument. The feelings that are evoked by the sculpture are different depending on “your specific cultural background [and] will shape your own specific response” (Wysocki and Lynch 274). This is also true of the symbolism that is applied to circular shapes. So, both of these factors are altered by our cultural backgrounds and the contrast created by the relationship between the weather and the sculpture help to illustrate this variation.

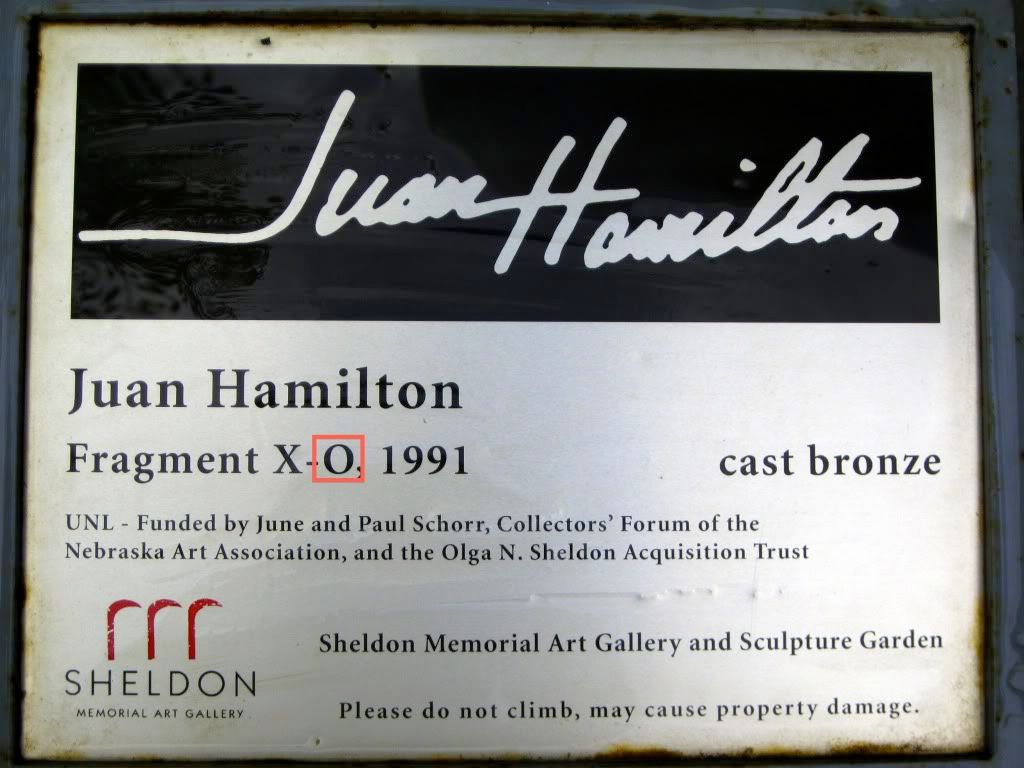

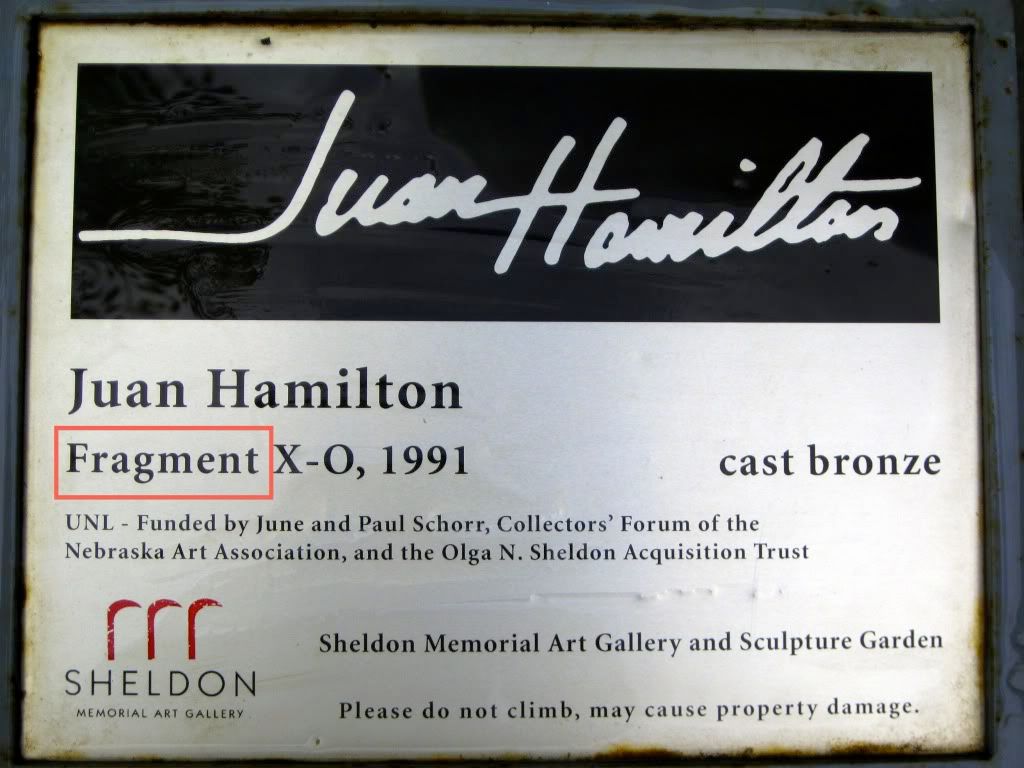

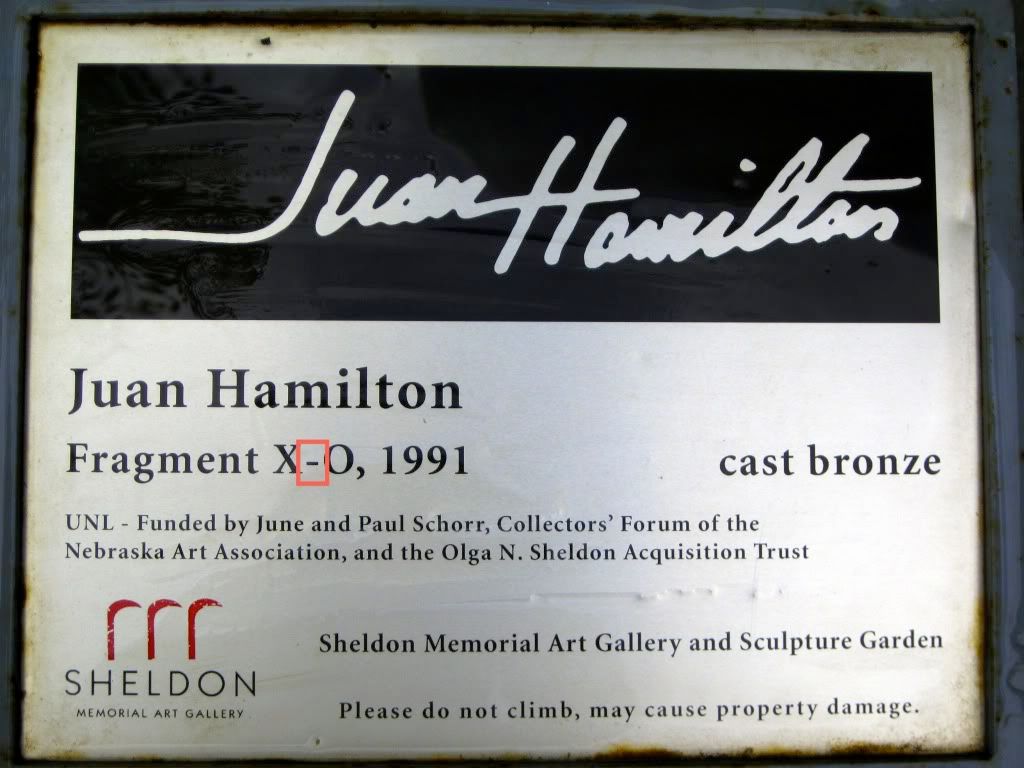

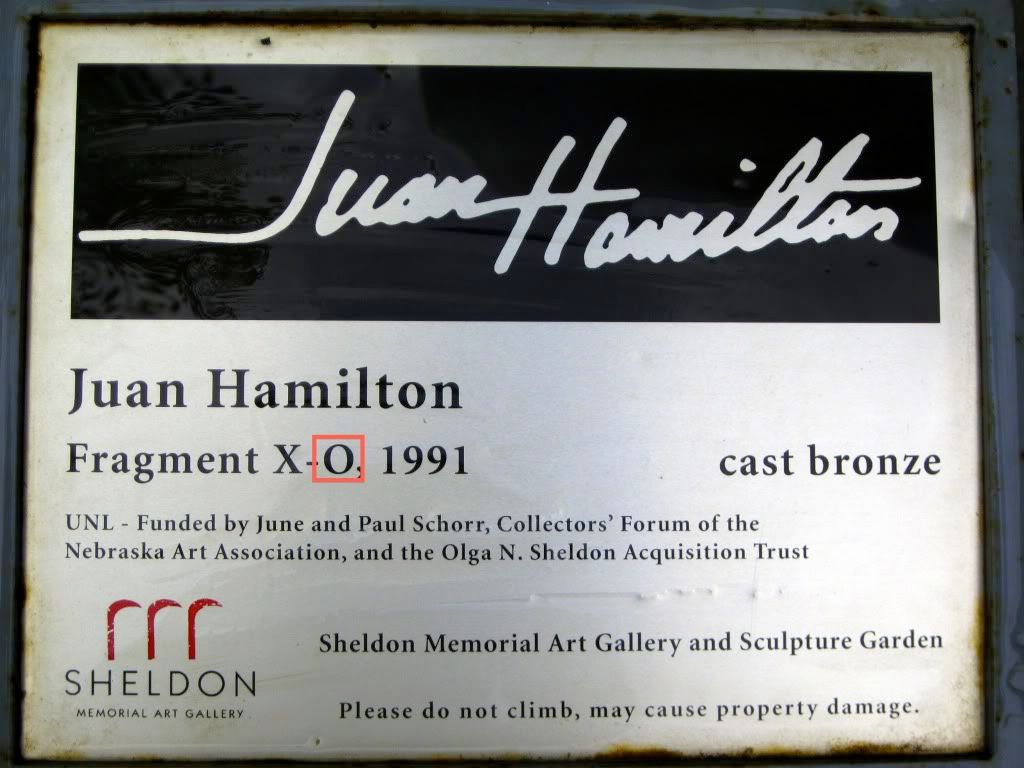

As the attention is drawn away from the physical form of the sculpture, the plaque card that accompanies the sculpture is considered. The most important part of this nameplate is the title of the particular sculpture, Fragment X-O. This is one of the most important and telling parts of the sculpture in terms of logos. This interaction between the words and the physical helps the focus of the audience to be placed on specific parts of the sculpture. Specifically in this case, the “words and [sculpture]… work together to have a larger effect than with alone has” (Wysocki and Lynch 302). From the beginning this portion of the sculpture helps to aid in the counterargument that the sculpture is working to create. In the short title, “fragment” is the first word. This word creates an immediate contrast between the sculpture and the title. In western culture, the circle or “O” typically symbolizes totality. The word “fragment” tosses this association to the side immediately and creates a distinct sense of discord between what is being seen and what is being read.

Next of all, the letter “X” appears in the title. This beckons the question, “where is the X?”. Well, it does not appear. This is the fragmented portion of the sculpture. The western association of the symbolism of X and O together are hugs and kisses, respectively. These are two forms of affection or salutation that usually work in tandem. This symbolism in western society also adds to the disparity that is created with the missing “X”. The unity that would have been created with the “X” appearing alongside the “O” has become void. Nonetheless, there are ways that this “X” can be added in using other materials outside of the sculpture itself. In respects to the framing aspect of this sculpture with the large empty center, another inanimate object could be introduced to the sculpture to complete it, or based on its size, a human could form the “X” by centering themselves in the hollow and spreading the legs and reaching the hands up to the sculpture. This interaction with its audience allows the audience to actively participate in completing symbolism of unity that is created by their society.

While the unity can be created by the audience that the title lacks, there is a unity in the title that can help connect the sculpture with the fragmented title. One of the most important, but unrecognized portions of the title is the en-dash that helps to join the “X” and the “O” together. This en-dash unifies the non-existent “X” and the present “O” just as the “O” signifies unity and completeness. While the sculpture is working to provide a counterargument in its interactions with the title and other elements, parts of the title are also working in contrast to create a similar counterargument.

The “O” is the most important part of the title. The “O” is what we have represented in this oversize bronze sculpture, shown to the left. But, there is a discontinuity between the letter “O” and what is presented. The letter “O” is perfect, complete and as tall as it is wide. It helps to form complete words and in many respects is also seen as a circle. This circle is used as a symbol in western society for completeness and unity. However, the sculpture, Fragment, is not perfect or unified in shape. It is wider than it is tall and parts of it are thicker than others. It is also not a perfect circle and does not even have the same color throughout. These imperfections are what help the make the argument. This disconnect between the “O” in the title and the “O” that is formed in the sculpture that detracts from the western symbolism of harmony that is applied to circles. This circle is not harmonious in its structure–it is imperfect and lopsided.

The shape of the sculpture also works as an appeal to logos in the “arrangement of elements”. This simple, but imperfect Fragment seems as though it should be easy to comprehend “because [it] does not ask much of visual effort from an audience” (Wysocki and Lynch 286). Nevertheless, it is this simplicity in the shape that asks the audience to look past the simplicity to see the argument. Again, there is a disparity created between what is expected of the sculpture and what is actually there that helps the further the counterargument that it is forming.

On the other hand, the visual hierarchy of logos created by the sculpture does actually work to create what is expected. The sculpture is placed in a clear hierarchy of the “element that first draws your attention being the largest and the darkest” (Wysocki and Lynch 287), however as this sculpture’s placement is examined further, it is noticed that it is placed upon a definitive concrete base. This base helps draw attention the sculpture by using contrast within the elements, namely between the highly structured, angled base and the soft lines of the sculpture. This contract between these elements draws attention to the sculpture and ultimately draws the audience in to the argument that it is presenting.

The placement of the Fragment X-O in the Sheldon sculpture garden adds to the overall argument that this sculpture is working to portray. Many of the other sculptures in the garden also embody parts of the hidden abstraction within Fragment such as Variable Wedge and Daimaru XV. These sculptures, which are in relative closeness to Fragment, add to the counterargument that it is creating for the symbolism of unity and completeness that is applied to the shape of the circle by western culture. This argument is created through the use of rhetorical and aesthetic tools, such as pathos and logos through title interaction and arrangement of elements. Now that this counterargument has been created by this particular sculpture, what are the other sculptures around us saying? From the rest of the sculptures in the Sheldon Art Gallery sculpture garden to other art forms in our museums, each is working to create its own communication with its audience. So, next time you are at your local museum see if you can interpret what that painting on the wall is saying to you. Does this piece of art have something interesting to say about our world as Fragment X-O does?

Works Cited

University of Nebraska- Lincoln. Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery and Sculpture Garden. 2010. 20 April 2010 .

University of Texas at Austin. Juan Hamilton. 2010. 20 April 2010 .

Wysocki, Anne Frances and Dennis A. Lynch. Compose, Design, Advocate. Pearson Education, Inc., 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment